Transforming Technology: Guiding Principles for Navigating Digital Evolution in Business

At loveholidays, when our customers contact us for help with their booking, they are now greeted by Sandy, our AI-powered virtual…

At loveholidays, when our customers contact us for help with their booking, they are now greeted by Sandy, our AI-powered virtual assistant. Sandy’s natural, conversational style replaces the need for ‘press 1 to make a payment’, providing immediate answers 65% of the time in live chat and 23% over the phone. This shift to AI-driven customer service has significantly boosted customer satisfaction and saved us millions of pounds.

The impact of this transformation highlights how technological innovation plays a critical role in business today. It illustrates how technological advancements can revolutionise businesses flexible enough to adopt them, proving this flexibility is a necessity for staying relevant and ensuring business survival.

According to a recent survey, 45% of CEOs don’t believe their business will be viable in 10 years time. Despite this, many organisations lack the essential investment in their technology platform that enables them to adapt. This short-term decision-making leads to a progressively expanding divide between business objectives and the flexibility required to achieve them, known as “technical debt”. Ignoring this debt will ultimately require a comprehensive “technology transformation” — an organisation-wide effort to tackle foundational challenges and realign the company’s strategic path.

The urgency of technological adaptation is apparent, with businesses worldwide investing a staggering $1.3 trillion annually in digital transformation projects. Yet, the path is fraught with challenges — 84% of these initiatives fail and 70% do not deliver the expected results. This stark reality underscores the need for an effective approach to technological change.

Over the last 15 years as a CTO, I have helped navigate two extensive technology transformations that have bucked this trend and witnessed first-hand their impact on the business results. The first instance was with Uswitch (a UK price comparison site), which saw a remarkable evolution from a modest £5 million acquisition to becoming part of a vast £2.2 billion delisting. The second was with the previously mentioned loveholidays, an online travel agent (OTA) whose technology investment during the COVID pandemic enabled it to not only move ahead of its closest competitor but to grow to triple its size.

My experience has underscored the critical role of a robust technological foundation in a company’s success. However, more importantly, it’s shown that getting technology right is not a technology problem — it’s a company problem. In addressing this broader challenge, I’ve identified three principles pivotal to a successful technological transformation:

Aligning organisational structure and technology architecture

Focusing technology teams on business outcomes

Creating an environment where people can ‘leave a footprint’

These principles form the backbone of this article.

#1 A modern architecture requires a modern business

In 2019, loveholidays was awarded the illustrious position at the top of The Sunday Times Profit Track 100, making it the fastest-growing company in the UK. That same year, I joined to help ensure the technology provided a strong enough foundation for its ambitious growth targets.

Even during the interview process, it was clear that much of loveholidays’ success was due to the insatiable drive of the founding CEO. He was obsessive over every detail of the business, with a laser focus on “building a moat” and staying ahead of the competition.

I vividly remember one of our first discussions about his approach. He was sitting in his office, which looked out over the development team, as he described himself as the “conductor of an orchestra.” He stressed the importance of going through every detail of a team’s work, questioning each decision, and controlling what was next with a list of prioritised tasks.

This kind of intense focus is essential for a start-up. At this stage of a business, you do not have the luxury or capacity to think too far ahead. You’re always a few bad decisions away from disaster — bear in mind 60% of all new businesses fail in the first three years in the UK. Therefore, keeping a new business going requires making decisions for the short term, cutting corners and doing a lot more with less.

However, I was there not to help the business get going but to help it achieve the next level of ambition. My experience scaling Uswitch, which got me the job as CTO, also made me acutely aware that getting to the next stage required a different approach.

Uswitch is a company with a rich history. Founded by the late Queen’s cousin as the energy markets deregulated, its rapid growth saw it sold for a price similar to Liverpool Football Club in 2006: ~£300 million. Failure to adapt its technology in response to a changing market resulted in the company I worked at picking it up for just £5 million.

It took us two years to rebuild the technology. This investment not only got it back on track but, over my 10-year tenure as CTO, served as the foundation for innovation that made Uswitch market-leading across several product categories and helped drive the three subsequent exits. One thing that became clear during this time was the critical relationship between a company’s structure and technology architecture.

We arranged our teams around business problems, not projects, to provide teams ownership of discrete systems. The resulting loosely coupled architecture allowed us to deliver in parallel across multiple areas, each balancing the delivery of strategic projects with the engineering excellence required to avoid technical debt.

Structure impacts technology

The understanding that how a company organises itself influences its technology isn’t a new observation — it was identified in the early days of computer science by Melvin Conway. He coined a law that, to paraphrase, stated, “the structure of the software will mirror the structure of the organisation that built it.”

One of the first things I did in the role at loveholidays was to work alongside the engineering teams to understand the systems. I observed a complex and monolithic architecture without the technical excellence required to scale. It reflected centralised “orchestral” control and short-term technical decisions needed at the early stages of growth. As a result, the teams struggled to meet the increasing business demands. Adding new capability was difficult, changes were risky and the systems needed more observability to respond before outages occurred.

At this point, I didn’t know whether to be worried about the enormity of the challenge or excited about the impact I could have. My experience turning around Uswitch gave me confidence that we could improve the situation. I might have been less optimistic if I’d seen a report conducted a few months before I joined, claiming “the platform would never scale”.

They were almost proved right in my first winter there.

Peak holiday booking season for travel starts on Boxing Day, and during the miserably wet winter of 2019, everyone in the UK seemed to be searching for a holiday. Unfortunately, our website could not cope with the volume of customers and every evening it would go down under the load. We were losing millions of pounds worth of bookings and degrading customer trust.

I remember talking to George, the VP of Engineering, late one evening on Slack and him listing all the architectural system changes we needed to prevent this. He told me we urgently needed to break the monolith into smaller systems and focus the team on improving them. At this moment, I knew we had to start changing the business structure to have a chance of making this happen.

Reverse engineering Conway’s law

Shortly after I started at loveholidays, the founding CEO told me his plans to leave. It was a shock, as I had joined because of his infectious enthusiasm, but meeting our new CEO gave me new cause for optimism. Across our many subsequent conversations, we agreed that scaling the business required us to stop thinking of ourselves as “a travel company that uses tech” and instead refocus as “a tech company that just happens to be in travel.”

He permitted me to spend the next month with the executive team, evolving the operating model and prioritising the long-term value of technical excellence. Our new structure reflected the architecture George had described. The intent was to reverse engineer Cowway’s law — creating the organisation that would produce the systems we desired.

To implement this, we created cross-functional teams around business problems and partnered them with the commercial teams. This new structure was more akin to a jazz band than an orchestra, with expert teams, each now able to work independently towards the goals set by the CEO.

This approach has had a transformative business impact.

The teams could now address the many problems identified in parallel. Boundaries between systems emerged where none existed before, helping to reinforce a more service-based architecture and enabling the teams to scale parts independently and optimally. The structure also provided the ability to apply different strategies depending on the business problem and introduce specialist skills to help accelerate these improvements.

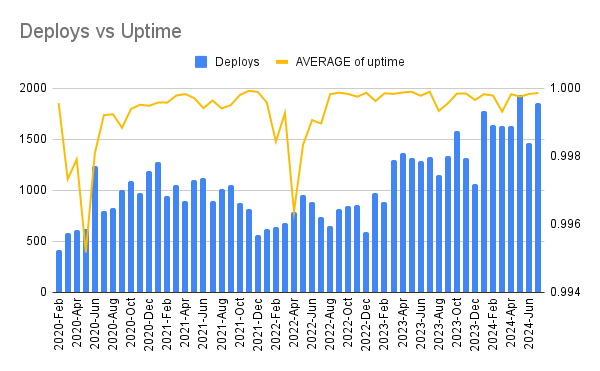

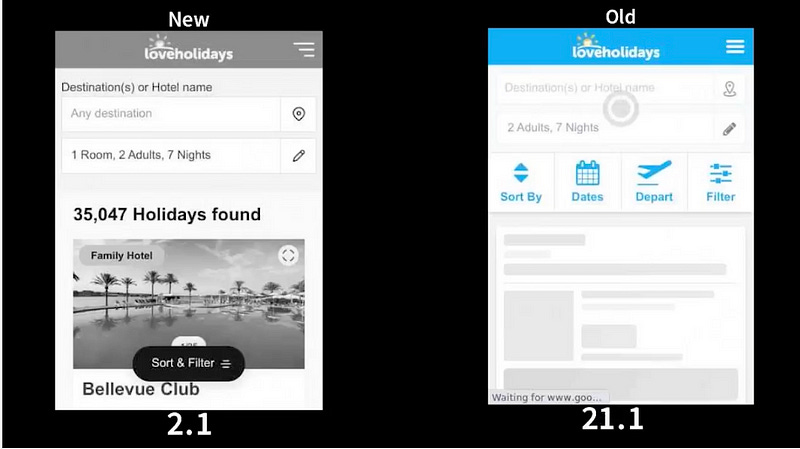

The result has been that the platform that “could never scale” now handles traffic many times that of 2019. Last January, we served more traffic in that first month of the year than we did for the whole of 2019, with no downtime for our customers. This year, we hit record booking numbers twice without any issues. Not only that, but we have increased the flexibility of the platform — we are now making 5 times the number of changes each month since we were able to track in 2019.

Understanding the link between an organisation’s business structure and system architecture is vital when transforming its technology and is an ongoing process. To help with this understanding, I regularly visualise the operating model to ensure I’m fully aware of the changes we make and the consequences for the architecture.

A similar principle applies to the technology team and its role in the business — to deliver large-scale changes, you must ensure the technology teams focus on and appreciate the commercial impact they can have.

#2 Focusing on business outcomes enables technical excellence

Something our CEO often reiterates when presenting is the importance of talking in terms that the business understands. He illustrates it with the parallels of visiting a doctor where you aren’t interested in hearing about how smart they are, where they got their degree or the procedure’s intricacies. You want them to give you confidence that they will make you better!

It’s an excellent lesson for any technical team to learn when interacting with the business: talk in a way the business can comprehend, in terms of outcomes rather than technology. However, I have learned that the ability to do this is a crucial enabler for delivering the significant changes required to transform a business’s technology.

Even with teams arranged around business problems with the responsibility and ownership of the systems that support them, there will still be significant changes to critical systems that require business buy-in. These projects are essential but complex, as the rationale for the change often requires specialist knowledge, which can usually be tacit or esoteric. The best approach to this is to explain the impact you’re trying to have.

The opportunity to do the right thing

This realisation first hit me when we sold Uswitch to Zoopla. As part of every sale, the buyer conducts due diligence on areas of the business, and, as an online marketplace, Uswich’s technology formed an essential asset of the acquisition. In previous sales, external advisors had run a box-ticking process that struggled to take into account some of the more cutting-edge approaches. But this time, Zoopla had sent their CTO.

I looked forward to explaining our technology to a fellow technologist and sharing ideas. I eagerly waited for him, whiteboard markers clutched in hand, ready to talk in detail about any aspect of the business. But just an hour later, he was leaving. I was shocked. He had been hard to read during the session, so I asked his thoughts. He replied, “This is amazing — who let you do this?”

Whilst the compliment played to my ego, the question of who “let me” do it also played on my mind. I knew the platform and its architecture were the core reasons for the business’s success. I was also lucky to work with a team that understood the value of getting the tech right.

This experience foreshadowed conversations with the CFO a year later following the acquisition that I still remember vividly.

What I thought would be a quick chat to get buy-in for one of those esoteric changes had degenerated into a heated debate about why developers aren’t fungible. I had made the mistake of trying to explain just how smart we were, and the less it worked, the faster I was waving my arms around. I was aware of how red and flustered my face was getting in contrast to the black paint on the walls. Luckily, we both knew the other wanted the best for the business and were willing to try and figure it out.

What changed the conversation was when I stopped talking about technology and started talking about the impact of the changes. I described how I wanted to create efficiencies to improve our margin percentage dramatically. We then spoke in a common language about the changes I wanted to make without the need for technical understanding. After the meeting, I agreed with the CFO that from now on, if I continued to talk to him about money, he wouldn’t try to speak to me about technology.

That stuck with me — if you show you’re taking accountability for your impact, it is much easier to gain the trust to do the required technical work.

The fastest website in travel

Before starting at loveholidays, I knew their “what, not where” search experience was a market differentiator. This unique feature allowed customers to detail the ideal holiday required and return tailored results without the usual constraints. It impacted every part of the purchasing customer journey, from inspiration to choosing the cheapest dates.

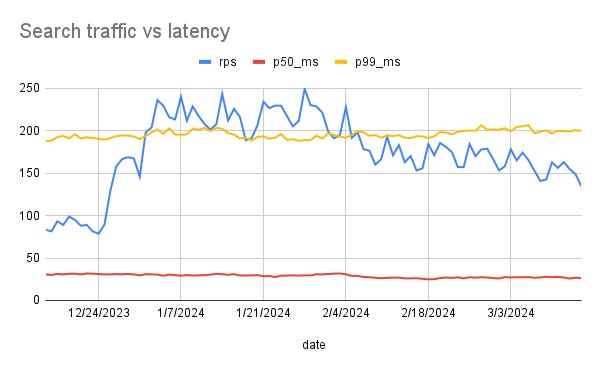

However, the slow speed of the search was also clear. This issue became painfully evident on a late-running, overcrowded commuter train home in my first month at loveholidays. I noticed someone struggling to browse our website through the forest of arms. Intrigued, I started watching and it quickly became apparent that the slow experience was the cause of much frustration, which ultimately led to him closing the site.

Addressing this issue was always going to be a significant challenge in our technology transformation. However, the extent of the challenge was only fully realised as the boundaries between the systems emerged.

Luckily, the engineering leadership at loveholidays did not repeat my mistakes.

George had joined loveholidays from a famous trading company in Chicago and brought unmatched experience in high-performance systems. After reviewing our search capability, it was clear that the open-source software the original team had innovatively adapted to enable this search was the cause of the problem. However, the fix was not straightforward and required the most esoteric technology changes — creating a proprietary in-memory data structure.

Instead of describing why this idea was so brilliant or how his background meant he knew what he was talking about, George sold the possibility of creating a “limitless search” for the business. He described how this change would impact the commercial elements of loveholidays, including scaling the number of hotels on our platform infinitely and drastically increasing the number of offers we could search across. George’s idea hooked the business.

But it was only half the story — the front-end platforms were also in a similar mess. The compounding of constant short-term decisions had created poorly architected systems that lacked an appreciation of the basics of website optimisation. The impact of this technical debt meant that even if we improved the search systems, these systems would limit the customer’s experience.

This challenge was tackled head-on by our now VP of Product, David Annez, with his customary relentless and unwavering style. Even with his industry-recognised track record at the forefront of web performance, he didn’t appeal to authority or talk in jargon. Instead, he described the correlation between speed and conversion, leaning heavily on real-world examples from previous companies and loveholidays data. This argument, supplemented with compelling data around the impact on our SEO rankings, got buy-in for the work (or at least sceptical acceptance) even from board members wary of investing any effort in technology improvements.

The impact of this work had enormous implications for the business.

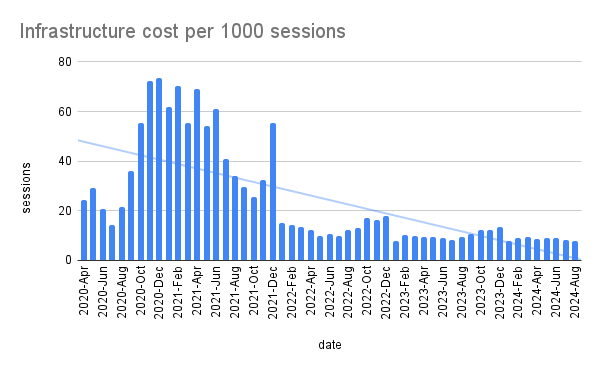

We have doubled the number of hotels we offer and increased the package combinations we process daily from 250 million to over 6 trillion. In addition, the speed at which you can search these offers is now more akin to Google or Amazon. We consistently return results in under 150 milliseconds and have made page speed 50 times faster. All of this has helped us reach record conversion rates and profitability levels for the business.

These improvements mean the person on the train would now see almost instant results rather than a frustrating loading indicator for 30 seconds.

I don’t believe anyone would have “let” George or David complete a migration like this if they hadn’t built the confidence to deliver it by talking about the impact that they were looking to have.

#3 Allow people to leave a footprint

Transforming an organisation’s technology is a challenge that requires years of concerted effort — in fact, it’s never truly finished. There are many ups and downs so sustaining focus and the motivation to progress is critical to success.

In the early years of Uswitch, I discussed the factors that influence motivation with my mentor. As always, I thought the problems I faced were unique, but he had seen them many times before — this was no different. In his usual enigmatic way, he described the difference between what motivates people using simple analogies while sipping a cappuccino and smoking a cigarette.

One particular description that immediately resonated was his description of the drive to build something — to look back and say, “We did this”. He summarised this as “leaving a footprint”.

This discussion clarified what I had known intuitively — the importance of having people lead the transformation who are motivated by building something. Their focus on creating something drives them to take responsibility, take ownership, learn, and adapt to changing requirements, which is essential for success.

Ceci n’est pas une banane

The concept of “leaving a footprint” resonated with me because I am one of those people for whom this matters. Looking back at my career decisions, I see that this desire has been behind my choices. The most influential was when I decided to leave the consultancy world and join a start-up.

At the time, I was working on a project that felt like an Adam Smith division of labour dystopian developer nightmare. Our team’s job was limited to taking data from the previous team, adding different data to it and then testing that the data was there.

I knew I had much more to give.

This desire gave me the push I needed to find a role where I could build something I was proud of. I followed a friend to a start-up, Forward (née TrafficBroker). There, the founder, Neil Hutchinson, believed in getting people to own problems, and I finally got the opportunity to be responsible for what I built.

The lessons from this experience fundamentally changed how I thought about technology. My approach became less academic and instead guided by customer business goals. It forced me to think more creatively, see the bigger picture and learn new skills to deliver the required outcome.

Steve Jobs described this realisation as “seeing the banana in 3D.” If you only focus on one element, like technology, and never have to deal with the results, you only ever develop a 2D view of the world. To “taste the banana” requires accumulating the learnings and scar tissue that only comes from owning your impact over an extended period.

A characteristic of an environment that allows people to leave a footprint is achieving success in unexpected ways. At Forward, the acquisition of Uswitch exemplified this unexpected success. As a consequence of working on the transformation, Neil offered me the role of CTO. I accepted, even though I had turned down opportunities before, as I saw it as an opportunity to build an environment where technology people could make a difference.

At Uswitch, the same approach yielded success in similarly unexpected ways. Examples included speaking to the EU in Brussels about the success of a bill-scanning app and building the first B2B data product in the energy market.

However, each success was only possible because people wanted to “leave a footprint” and were willing to take responsibility to make it happen. So when I accepted the role at loveholidays, I knew the people were as important as the environment.

Everyone can build with AI

Shortly after I started, my colleague Eugene Neale reached out to chat. I was excited because he loves to leave a footprint (not just because he’s a massive hippy who often walks around the office without shoes). When we talked, he passionately described how he had been experimenting with contact centre AI and saw an opportunity in travel to build something unique.

Our contact centre at the time had suffered years of underinvestment in its systems and infrastructure. The office embodied this with its ancient desktop computers and massive CRT monitors covered in laminated instructions.

However, with a builder mindset, the platform’s lack of maturity suddenly became an opportunity — he could replace vendors and move to more cutting-edge platforms to bring his vision to life.

A pivotal moment came during COVID. We had received 10 times our average yearly volume in a month and needed help coping. Not willing to let a good crisis go to waste, his team developed the first version of Sandy to help customers receive a refund. Since then, Sandy’s capability has expanded through constant iteration to assist customers with over 500 unique types of requests.

Eugene took responsibility for part of the transformation and created a service with a higher CSAT, saving the business around £3 million in 2023 alone.

It’s also interesting that Eugene was the first to show how, with the help of AI, non-technology roles can help with the technology transformation.

A great example was how he helped Juliana Smith move from our QA team in the contact centre to Conversational Design in our AI team. Her experience listening to countless customer calls was vital to designing the flow of conversations that support our customers appropriately.

When she joined loveholidays five years ago, Juliana couldn’t possibly have imagined that she would end up here. She has built something to be proud of and her role in the organisation has helped us ensure that Sandy takes care of simple queries, freeing up our contact centre agents for solving the complex cases that need extra sensitivity and compassion.

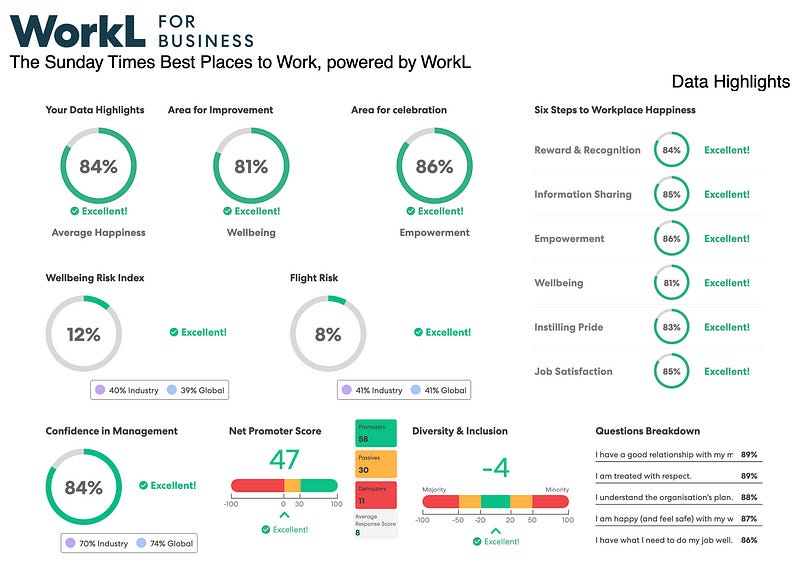

Sandy is just one example of how we are building on top of the technology transformation and realise value in surprising ways. It was only possible with the motivation and desire of people who want to make a difference. What is most personally satisfying is the culture we create in the business, where everyone can leave a footprint and build something they are proud of. We have seen it consistently in our engagement surveys and it’s helped us gain recognition on The Sunday Times 100 Best Places to Work.

Conclusion: Navigating the Digital Evolution

My mentor always told me it doesn’t count if you only scale one business — like skateboarding tricks, it takes “two to make it true”. When you see things more than once, patterns emerge. It’s become clear to me that successful technology transformation is not about implementing the newest systems or adopting the latest tools. It’s about fundamentally aligning your organisation’s structure, focus and culture with your technological goals.

The three guiding principles we’ve discussed provide a roadmap for leaders navigating this complex landscape:

Align your business structure with your desired technology architecture. By reverse-engineering Conway’s Law, you create an environment where your organisational design naturally fosters the technological systems you need.

Focus relentlessly on business outcomes. When technology teams can articulate their work in terms of tangible business impact, they gain the trust and support needed to implement far-reaching changes.

Create an environment where people can “leave a footprint.” Empowering your team to take ownership and build something they’re proud of drives innovation and sustains motivation through long-term transformation efforts.

These principles are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. They can propel an organisation forward in its digital evolution when applied together. At loveholidays, we’ve seen first-hand how this approach has enabled us to not only keep pace with change but also lead it.

As we look to the future, these principles will become even more crucial as AI and other emerging technologies reshape the business landscape. They provide a flexible framework that can adapt to new challenges and opportunities, ensuring that technological transformation remains aligned with business goals and human potential.

Anyone embarking on a digital transformation should consider how these principles might apply to their organisation. Start by examining your current structure, refocusing your tech teams on business outcomes with clear business KPIs, and cultivating an environment where innovation can thrive that you measure and react to regularly. Remember, though, that it is a continuous process that requires patience, adaptability and a willingness to learn from successes and setbacks.